Alchemical Motifs in Chrétien’s Romances

On Chrétien de Troyes (fl.1160–1191) as an artful celebrator, Freeman (1979) writes: Renowned experts and a few enlightened laymen now concur that artificers – be they weavers, seamstresses, blacksmiths, sculptors, architects, apothecaries, even sorceresses – all engage in variants of the same fundamental processes whereby basic materials, though artfully reshaped according to the tastes and abilities of their makers, nonetheless betray the authoritative influence of earlier masters when submitted to the scrutiny of informed scholars… Now and then, we may even find an artful celebrator of the work of others.8

Progressing from a previous article concerning the goldsmith as a possible pseudonym for alchemist amongst a condemned Amalrician cleric16 – to an attempt to separate the subtle from the gross within a twelfth-century literary territory – we are, as with our approach to the article on the Templars,17 on thin scholarly ice. If we first separate the earth from the fire, the ice may support the alembic over the cold flame of esoteric decipherment; otherwise it may be prone to crack under the weight of imaginative projections, or the brazen fire of fictional speculations.

And, this is exactly what the modern scholastic trend purports to have happened: If modern mystery interpretations are nothing more than a projection of meaning or belief (Wood, 2012)21 then, while not dismissing out of hand some undeniable alchemical or otherwise mystical elements in the works of Chrétien de Troyes and Wolfram von Eschenbach (c.1160–1220), these motifs are considered mere “window dressing” to an imaginative literary output under a fictional genre of medieval entertainment (Barber, 2004).1 The key is rather in abeyance to any hidden transmission to unlock.

In order to tease out the artificers and their earlier masters then, this thesis will draw upon a more applicable analysis for alchemical motifs and philosophical conventions in Chrétien’s romances by such informed scholars as Braid (2011),2 Lotze (2013)11 and Reichert (2003);15 the latter references a fair proportion of un-translated French studies.

Patrons, sources and Influences

Chrétien was certainly under a lot of friction through the “courser elements” decreed by his earlier patronage. The demands of secular court life (not unlike the modern subscriber to Netflix) craved the kind of troubadour romances of courtly love amid a backdrop of crusading epics. His first supposed patron, Marie of Champagne (1145–1198), would have been familiar with the older compendium of romances in Chansons de Geste (songs of heroic deeds) and the Breton poet Béroul’s, Roman de Tristan (1150–70). These tales, sung or recited by court jongleurs, would include such themes as the violent, crusading and somewhat anti-infidel (Muslim) Chansons de Roland (c.1100) or, the illicit Tristan and Iseult.15

To separate the subtle from the gross, Chrétien’s use of Speculum principis and lectoris as a literary device was, by use of hyperbole and metonymy, a stratagem to mirror moral precepts from the commissioned narrative and reorientate the tastes of his readers.15

For instance, it was from the book Chrétien claims to have found in the library of the Cathedral of Saint-Pierre de Beauvais that, somewhat in moral contradistinction to Tristan and Iseult, he modelled Cligès. And, as an avid interpreter of Ovid, Chrétien makes of his Cligès an oriental disguised in western dress; quite the reverse of the western European crusader glorified as an oriental in the Chansons de Geste.15

This also brings to the fore Chrétien’s disguise? His postposition of origin – de Troyes – had a noted Jewish community. This leads Holmes (1947), to suggests that a Christian convert from Judaism wouldoften take such a name as Crestianus; that Chrétien was one known as Crestiens li Gois.10

If he was in exile, Reichert at least considers the name Chrétien to indicate a New Christian. Benton (1959) had stipulated that ecclesiastical duties with a prebend (salary) would accompany the adoption of the new name. Conterminously, the patron would travel to an institution, such as an abbey, to seek out relevant manuscripts, along with those writers capable of literary translation or re-interpretation.15

Alternatively, since there are no census records for Chrétien at the court of Champagne, or archival records for his time spent at the court of Phillip d’ Alsace, Chrétien may have been a cleric in breach of his vows.15

Of note is a subtle reference to the quadrivium in Érec et Énide, whereby the curriculum of Geometry, Arithmetic, Music and Astronomy is woven by faries into the hem of Érec’s robe.15 Indeed, Chrétien’s use of speculum literary devices may have been learned through the Schools of Paris, under the speculum literature developed out of Honorius Augustodunensis’ (c.1080–1154), Speculum vel imago mundi.

Braid emphasises that the scholarly trend at the time was to visit Northern Spain and Sicily where Arabic speaking Christians and Jews were already elucidating the Greek sciences and philosophies, from Arabic works.2

On the other hand, Reichert refers to the scribal Muslim captives working in the Benedictine and Clunaic monasteries along the pilgrimage route through Spain. As a source of transmission, the conduit was for Islamic religious, philosophical and alchemical texts to reach Plantagenet territories of Champagne, Aquitaine and Flanders.15

Contrarily, the reference to textores for weavers in these north-western European territories, insinuated their heretical status as co-fraternities.15 Even supposing Chrétien had no access to their mystical or alchemical doctrines, the weavers were certainly represented as prisoners in the Conte du Graal, or the captive damsels in Chevalier au Lion who weave cloths of silk and gold.7

While in token agreement to undeniable biblical references appearing Chrétien’s romances, Reichert considers that Wolfram’s reference to Master Chrétien (‘Master’ can be a pseudonym for alchemist15) comes closer to an Arabic source of common origin for his works. After all, Wolfram claimed that Chrétien did no justice to the original Toledoan source in Flegetanis, through Kyot the Provençal.15 Incidentally, Chrétien claimed his source book for Le Conte du grail was given to him by Phillip d’Alsace.

There were two early important works on alchemy by Abu Maslama al-Mayriti of Madrid entitled the el Rutbat al-Hakim (c. 1047) and Gayat al-Hakim (1056). The latter was later translated in Castillan as the Picatrix.2

The Tabula Smaragdina (Emerald Tablet) that was available to the students of Thierry of Chartres (d.1150) from the middle of the C12th was of a Latin text translated in Spain, by Hugo of Santalla (fl. early C12th).2

Lotze considers that Chrétien was familiar with the Turba Philosophorum. Despite a later C16th date of Latin translation, Ruska (1931) concluded that the Turba was known in Latin at the beginning of the 12th century.2

Finally, Robert of Chester (Latin: Robertus Castrensis) translated Morienus’ Liber de compositione alchemiae (The Book of the Composition of Alchemy) from Arabic, in 1144.2

Prior to this Latinisation, we can look to The Brethren of Purity (Ikhwan al-Safi, C10th) – an Ismā‘īlī Sufi sect who were based in the Andalusian (southern Iberian Peninsular) territory of Sierra de Córdoba.2 Al-Rudhabari (d.934) remarked, The Sufi is the one who wears wool on top of purity; the same might be said of Chrétien’s Perceval, in Le Conte du Graal.

In praise of Hermes Trismegistus as philosopher and prophet, the Brethren of Purity were inheritors of the Jabiran corpus: Jābir ibn Hayyān (Latin: Geber) was supposedly a pupil of Ja‘far al-Sādiq (d.765).2 It may be pertinent to speculate that, putting aside the Christian gloss and anachronism, Wolfram’s Kyot is a pseudonym for Jābir ibn Hayyān; Flegitanis would be Ja‘far al-Sādiq, his master. While others may have proposed alternatives, the suggestion is made for what it is worth.

The Brethren of Purity seem to provide a median source of transmission between purely scientific alchemical texts divorced from any mystical or philosophical connotations, and on the other hand, Sufi Illuminism or Avicennist philosophy; the latter may not have necessarily approved of alchemy.2 From this median pivotal stance, the Illuminist (ishraqi) philosophical tradition of the alchemist Shihab al-Din al-Suhrawardi (1154–1191) could be seen to have culminated through his writings.

Alchemical Romance

Reichert conjectures that Chrétien’s romances functionon two levels: the first alludes to the moral system of twelfth-century social and literary practices where the protagonist finds only the worst aspects of twelfth-century “chevalerie” and “clergie”, represented by King Arthur’s court. Secondly,Chrétiencounters this by his own moral prescriptions, partly through alchemical figures and symbols.15

Lotze alludes to the prologue of the first of Chrétien’s romances, Érec et Énide, whereby the alchemical process sounds with a proverb:

The peasant in his proverb says that one might find oneself holding in contempt something that is worth much more than one believes. (Vs. 1–5)

Likewise the coniunctio (alchemical union) mentioned throughout the Turba alludes tovs. 16, where the Old French conjunture translates to conjuncture, ‘join together.’

A bien dire et a bien aprendre, Et trait [d’]un

conte d’aventure Une mout bele conjunture.

To speak well and to learn well, And treat one

adventure tale with, A beautiful conjuncture.11

There is, of course, the caveat of reading alchemical motifs into the romances that would not have been available to Chrétien: The via sicca (dry way) of Jābir (Geber) would represent the prime matter as gold, tin or copper that is immolated by fire, vitriol, antimony or aqua regia (nitric and hydrochloric acids) resulting in a calcination.9 The four alchemical stages that originated with Zosimos the Alchemist (Latin: Zosimus Alchemista, fl.C3rd–4th) were nigredo, albedo, citrinitas and rubedo.

The via humida (wet or humid way) developed by Basil Valentine (fl.c.1413) would achieve the same reduction of prime matter through putrefaction to dark ashes, again symbolised by the nigredo. By the time of George Ripley (c.1415–1490), the conflation of anthropomorphic, animal and bird symbolism added to an extended seven or twelve alchemical stages, keys or gates.

Érec et Énide (Erec and Enide)

Having already spurned Arthur’s traditional springtime hunt of the white stag, the romance begins with the Aqua vitae (water of life) of the Turba expressed in Érec’s tunic of splendid flowered silk, that is made in Constantinople. Inappropriately dressed (thus marking him as a candidate for initiation), Érec decides to ride alongside the Queen Guinevere and her damsel-in-waiting for an observational excursion into the woods.11

What they do encounter in the forest turns out to herald Érec’s alchemical process. It is the state of helpless dissolution following the abuse Guinevere’s damsel, and then the unarmed Érec himself, receive from a churlish and malicious dwarf who accompanies a wandering armed Knight and his Lady.

And before him [the knight] went a sorry hack

With a dwarf mounted on its back,

And in his hand the dwarf carried

A lash with every strand knotted.5

Resting from pursuit until he can gain arms, Érec encounters for the first time the yet un-named Énide. She is his host the vavasor’s beautiful daughter, wearing a worn and tattered white linen shift. The significance here is the albedo (whitening)stage whereby the Aludel is an alchemical apparatus of sublimation, with openings at the side.

But the dress was so very old

That its sides were full of holes.11

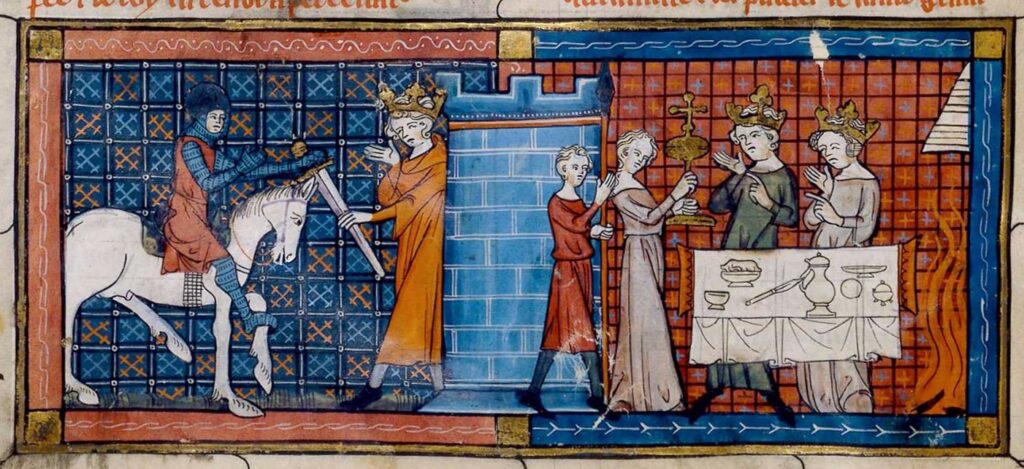

It is prior to the sparrowhawk contest that Érec and the vavasor visit the hermit who performs a Mass of the Holy Spirit. This triggers the process of sublimation: Érec’s award to Énide of the hard-won sparrowhawk emblematises, in alchemical terms, the spirit finding the body.11

Let it remain in that trituration or decocting until the spirit penetrate the body. For by this regimen the spirit is made corporeal, and the body is changed into a spirit. (Turba, Eighteenth Dictum)14

The philosophers of the Turba would have recognised repeated dissolutions: that a second testing phase must follow for the initial beautiful conjucture of their physical marriage to develop into the final coronation scene: the true coniunctio, of soul and spirit.11

Whereas it is the purification of the body that is at stake, Énide’s subsequent degradation is taken in consequence of Érec’s vanity and pride.

Stir up war between copper and quicksilver, until they go to destruction and are corrupted, because when the copper conceives the quicksilver it coagulates it, but when the quicksilver conceives the copper, the copper is congealed into earth; stir up, therefore, a fight between them; destroy the body of the copper until it becomes a powder. But conjoin the male to the female, which are vapour and quicksilver, until the male and the female become Ethel, for he who changes them into spirit by means of Ethel, and next makes them red, tinges every body, because, when by diligent cooking ye pound the body, ye extract a pure, spiritual, and sublime soul therefrom, which tinges every body. (Turba, Forty Second Dictum)14

Despite this war of attrition, the alternating diurnal sleeping patterns of the two protagonists while on the road are alluded to pertain to the more purifying actions of this powdered copper (sulphur) and vaporous quicksilver – as Sun by day and Moon by might.11

Érec bids his lady sleep while he

Undertakes to keep the watch.

She replies that she will not,

It is not right, should not be so;

He must sleep who needs it though.5

Cligès

If Cliges mother Soredamor is etymologically the red molting bird, then her daughter in law Fénice is the red phoenix; the romance indeed reads as a process of alchemical transformation and resurrection.2,15 To escape her arranged marriage to the old Duke, Fénice fains death by having her nursemaid Thessala make her unconscious through a herbal draft. For her to elope with Cliges, the Mason John builds an hermetically-sealed tower – alembic or tower furnace – whereby they can achieve coniunctio. However, prior to Fénice being buried alive in the sepulchre, a stage of putrefaction begins with the Duke’s physicians beating her “corpse” with thongs and trying to roast her over a grill, before pouring molten lead into her hands.7

It is also convenient for you to know this, that if you shall not perfectly cleanse the unclean body, nor shall not dry it, nor make it perfectly white, and shall not send its soul into it, and shall not take away all the stink of it, until after its cleansing the tincture may fall into it, that then you have directed nothing well in this Magistery.

Wherefore put a gentle fire unto it, and let it burn the space of its days with all equal heat: for the body consumes itself by the heat of the fire. Creeping in the fire: for if Eudica (the faeces of glass) be put unto them, it will free from all combustion those bodies that are changed into Earth. For bodies are presently burned, after they retain their souls no longer.

Know therefore, that the unclean body is Lead, which by another name is interpreted Assrop, but the clean body is tin, which by another name is also called sand. The green lion is glass, also Almagra is Laton, although before it is said to be red Earth. (Morienus, Book of Composition)12

On another level, Reichert suggests that Chrétien meant to emphasise a comparison between the incompetence of western European physicians against Fénice’s nursemaid Thessala (c.f. Medea the Thessalonian), who is learned in Greek medical science.15

Yvain ou le Chevalier au Lion (Yvain, or the Knight of the Lion)

Prior to Yvain’s more successful attempt, Calogrenant’s failure at the fountain is through the misuse of the potential creative force inherent in prima materia (prime matter), mostly through worldly ambition. The creative force is represented by the alchemical motif of the bulls, but their guardian acts as a guide and directs Yvain to a fountain next to which hangs a gold basin.15

Never was there so dense a shower

That even a drop of rain could pass6

Since the alchemists would represent the prima materia in variant guises, the gold basin by the fountain may be such. The pierced emerald stone, after being filled with rainwater, would be an hermetically-sealed alembic, or retort.

Moreover, Yvain uses the gold basin, as per the Turba, to pour the Aqua vitae (water of life) from the fountain upon the pierced Emerald Tablet.

While the fountain I saw there

Like boiling water it seethed;

The stone was emerald, I believe,

Pierced like a cask all through,

With four rubies beneath it too,

More radiant and a deeper red

Than the sun risen from its bed.6

Returning briefly to the prologue ofÉrec et Énide, Lotze accords that the something that is worth much more than one believes translates from the Old French, Tel Chose to Latin, Illa res. The Latin Illa res isa term used in the Turba for the prima materia. Therefore that something (tel chose) is a stone and not a stone (Quae lapis est et non lapis).

Li vilains dit a son respit

Que tel chose a l’en en despit,

Qui mout vaut mieuz que l’en ne cuide.

The peasant in his proverb says that one might

find oneself holding in contempt something that

is worth much more than one believes. Vs. 1-3 [trans. C.W. Carroll]11

In a sense then, the rubies embedded under the emerald stone could be the result of rubification, or again a depiction of the state of prima materia, that is a stone and not a stone.

I tell you that it turns the sea itself into red and the colour of gold. Know ye also that gold is not turned into redness save by Permanent Water, because Nature rejoices in Nature. (Turba, Eleventh Dictum)14

Rubigo is according to the work, because it is from gold alone. (Turba, Forty sixth Dictum)14

Howbeit, the fountain represents dissolution in the alembic under the action of sulphur and mercury – symbolised in alchemy by the Sun and Moon. The first beautiful conjuncture is Yvain’s subsequent marriage to Laudine – the Lady of the Fountain.

So when the male and the female are conjoined there is not produced a volatile wife, but a spiritual composite. (Turba, Seventeenth Dictum)14

Along with Arthur’s entourage, Gauvain/Gawain (Sun) now enters the realm and offers his service to Lunete (Moon). She returns his affections, so the Moon stage of albedo turns to the Sun of citrinitas; their hermaphroditic offspring is the philosophic mercury.9

Must here the sun’s position claim.

I speak of course of my Lord Gawain,

For chivalry does his form proclaim,

And he illumines it with his rays,

Just as the sun, at break of day,

Sheds his light, and illumines all

The places where his rays do fall.

And our damsel I call the moon,

For here there can be only one

Of such great aid and service.

I call her not so because of this

Merely, she so free from blame,

But because Lunete is her name.6

Yet Gauvain and Yvain soon abandon their ladies for Arthur’s realm. The rubido is halted. It is only after many trials – a second cycle of putrifaction – that Yvain is reconciled with Laudine. The rubido of the true coniunctio is then consummated as their final alchemical marriage.

Venerate the king [Citrine] and his wife, and do not burn them, since you know not when you may have need of these things, which improve the king and his wife. Cook them, therefore, until they become black, then white, afterwards red, and finally until a tingeing venom is produced. (Turba, Twenty Ninth Dictum)14

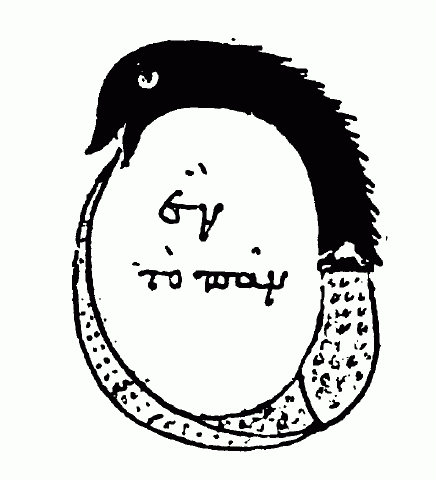

The title of the romance is taken from a scene some time after Yvain is restored to health after realising his abandonment of Laudine. It is in the act of cutting off the tip of the lion’s tail with his sword to save it from being devoured by a serpent, that is reminiscent of the ouroborus. At this point Reichert suggests that Chrétien had brought his four romances full circle.15

He saw a lion, in that open space,

And a serpent gripped it by the tail,

Striking its rear, like a fiery flail,

Scorching the beast with hot flame.6

She likewise draws attention to the Tabula Smaragdina and suggests that Yvain’s actions in preventing the serpent from devouring the lion represents a failure of the purification process: If by via sicca the fiery serpent – volatile mercury – is prevented from acting upon the prima materia – symbolised by the lion – then indeed Reichert is justified in her assertion that the arrest of the transmutation means that Yvain fails [for the time being] to achieve calcination and the purification of his soul.15

Separate the earth from the fire, the subtle and thin from the crude and [coarse], prudently, with modesty and wisdom

It [fire] ascends from earth to heaven, and descends again, new born, to the earth, taking unto itself thereby the power of the Above and the Below

For this [volatile mercury] by its fortitude snatches the palm from all other fortitude and power. For it is able to penetrate and subdue everything subtle and everything crude and hard. (Tabula Smaragdina)13

In this manner, therefore, ye are to rule your natures, namely, to dissolve in winter, to cook in spring, to coagulate in summer, and to gather and tinge the fruit in autumn. Having, therefore, given this example, rule the tingeing natures, but if ye err, blame no one save yourselves.(Turba, Seventeenth Dictum)14

Lancelot, le Chevalier de la Charrette (Lancelot, the Knight of the Cart)

Reichert now attempts to surmise how the symbolism in this romance is probably armorial rather than alchemical: The tower that becomes a prison for Guinevere is seen to reflect the imprisonment of Eleanor of Aquitaine. Chrétien saw her as Eve felenesse (Old French, treacherous or perfidious Eve), intending the pun while using the phrase to describe the dark and murky water running under the sword-bridge. Likewise, the lions or leopards guarding the sword-bridge are again taken to be Plantagenet armorial references; the guardant (sidelong with head facing outward) lion was known as a leopard in Plantagenet armorial bearings. Seen at a distance, the leopards may represent Chrétien’s distancing himself from the decadent Plantagenet court of Henry II, of which he may have spent time. Similarly, Lancelot’s ride on the Cart of Infamy may be Chrétien’s way of describing his experience under his patron Marie of Champagne; she commissioned the romance as a revenge upon Tristan and Iseult. Chrétien left Chevalier de la Charrette unfinished while simultaneously developing between 1177 and 1181, Yvain ou le Chevalier au Lion.15

Despite Reichert’s reticence, there still may be some parallel alchemical themes worthy of further investigation; not least the maiden who leads Lancelot to the fountain and comb, wound with strands of Guinevere’s golden hair.

The fountain, set amidst a meadow,

Fell to a stone basin below,

And on the stone, we must assume,

Someone had left, I know not whom,

A comb of ivory inlaid with gold,6

Perceval ou le Conte du Graal (Perceval, the Story of the Grail)

Another alchemical reference to the prima materia is Perceval’s acquired red armour – the biblical Adamah (red man) or Terra rubra (red earth) – whom he kills [by his javelin] in order for the philosopher’s stone to be born.15

And know, all ye disciples, that iron does not become rusty except by reason of this water, because it tinges the plates; it is then placed in the sun till it liquefies and is imbued, after which it is congealed. In these days it becomes rusty, but silence is better than this illumination. (Turba, Fifty Ninth Dictum)14

Perceval enters the red and green tent – tabernaculum of green, red and gold which radiates with light – where the awkward and uncultivated youth, after roughly kissing the damsel without her leave, prises the emerald ring from her finger.7,15

An eagle, gilded, at its crest.

By the sun the tent was blessed

Such that all the field was lit

With the light that shone from it.4

Reichert here draws attention to the Golden Eagle as a symbol of John the Evangelist, who is a revered figure in Arabic Alchemy, and collates the blazing red and green tent with Al-Ghazali’s (c.1058–1111), The Niche [Tabernacle] of Lights.15

Chrétien may have intended the damsel’s emerald ring as alluding to the Islamic Al-Khidr (Green one), or in proxy to the Tabula Smaragdina.

Till he spied a ring on her finger,

An emerald, and the stone did shine.4

What is most likely is that Perceval’s state of youthful volatility conspicuous by his grasping after outward appearances marks, the alchemical stage of the Green Lion. This stage precedes his acquisition of red armour, or reddening.

Ripley, in Medulla Alchimiae, wrote, the Green is a very immature or unripe thing, the Yellow is a more matured state of “our Unripe Gold,” the Red Lion is the perfect state, sometimes applied to the philosopher’s red stone, but more usually to ordinary gold.

Perceval approaches Gomemant’s castle where the latter, clad all in white, awaits the Red Knight’s arrival. The castle is surrounded by water, with an emphasis upon the blackness of the river.7,15

When ye see that the matter is entirely black, know that whiteness has been hidden in the belly of that blackness. Then it behoves you to extract that whiteness most subtly from that blackness, for ye know how to discern between them. But in the second decoction let that whiteness be placed in a vessel with its instruments, and let it be cooked gently until it become completely white. But when, O all ye seekers after this Art, ye shall perceive that whiteness appear and flowing over all, be certain that redness is hid in that whiteness! (Turba, Sixty Ninth Dictum)14

The Book of Composition gives: O good King, first it behoves you to know, that red fume, citrine fume, white fume, the green lion, Almagra, the uncleaness of death, blood Eudica, and stinking Earth [black], are those things in which the whole efficacy of this Magistery consists: which can by no means be done without these.12

Avicennist and Sufi Interpretations

To proceed with Le Conte du Graal leading up to the actual graal procession, Reichert attempts to etymologically unravel concepts that appear in translation. It is in the preceding romance that the name Y-vain would seem to mean an empty or sterile “Y.” In Latin, the letter Y was named I graeca or “Greek I.”15

Isadore of Seville (c.560–636) in his Etymologies (c.615–30) markedthe trace of the creative power of the Father in the letter “I”, in which is inscribed the symbol of divine transcendence in nature.Furthermore, Reichert’s translation of the word ‘vain’ in Old French bypasses the more common interpretations of “empty, weak, liquid and exhausted,” to confer meaning to the idea of barren or sterile land.15

Perceval fails to question the graal procession and the Gaste Terre (waste land) remains.

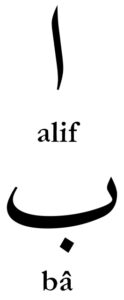

Consequently, the words of the hermit to Perceval that the lance-head that never staunched its flow of blood has its equivalent in the Sufi perception that when the Ink continues to flow from the divine Calame (reed-pen), Creation is still in progress: Therefore the “calligraphy” of the ‘lance’ and the ‘graal’ in the procession scene is redolent of the Arab letters Alif and bâ.15

To quote Suhwarardi:

Bi kana ma kana wa bi yakunu ma yakunu,

Whatever became, became through Me,

And whatever will become, will become through Me.

The essence of the essence is the dot under the letter “B[â]”.20

Furthermore, the Sufi saying Lisanak hisanak translates to Your tongue is your horse. Chrétien depicts Énide’s horse that is white and black and divided by green to be, again according to Reichert, a metonymy for language or speech; that the purpose of the letter Mim (the temporal prophet) is to release his horse, that is to speak.15

She continues, since it is from Jābir’s doctrine of the Balance of Letters that the letter Mim is ‘the one who speaks’ and the ‘Ayn is the ‘Silent One,’ then the eloquent speaker Gauvain repeatedly looses his horses, and Perceval is silent in front of the graal.15

In conclusion, i regret not being able to include all instances of Avicennist philosophy, Sufi Illuminism and alchemical motifs in the narrative of the romances. To read them in full, please refer to the referenced scholars.

However, we have observed an east to west gradalis19 of philosophical transmission in Suhwaradrian metonyms and a southern transmission of alchemical motifs; mirrored in a Christian narrative, they are shown to be consistent in purifying and transubstantiating Chrétien’s perception of western twelfth-century “chevalerie” and “clergie.” By surreptitiously bringing together these mystery streams, whatever may have been his true intentions, Chrétien was certainly a conduit of his Age.

That being said, by the Ex Oriente lux (light, out of the east),18 the West may not necessarily be decadent. To re-kindle its own light we should perhaps endeavour to move beyond Reichert’s observation that, for Chrétien at least, it simply serves as a kind of canvas upon which he embroiders his stories, only appropriating the original Celtic protagonists and motifs as they suit his narrative purposes.15 The Matter of Britain and related folkloric material will be explored in relation to Chrétien’s romances in a forthcoming article.

References

- Barber, Richard (2004) The Holy Grail: The History of a Legend, Penguin; New Ed edition (2 Dec. 2004)

- Braid, Angus. J., (2011) Mysticism and Heresy: Studies in Radical Religion in the Central Middle Ages (c.850-1210), WritersPrintShop; 1st Edition (26 Sept. 2011)

- De Troyes, Chrétien (1181-1190) Perceval: The Story of the Grail, trans. Bryant, Nigel, D. S. Brewer (1982)

- De Troyes, Chrétien (1181-1190) Perceval: The Story of the Grail, trans. Kline A. S, (The Arthurian Romances of Chrétien de Troyes), Independently published (5 April 2019)

- De Troyes, Chrétien (c.1170) Erec and Enide, trans. Kline A. S, (The Arthurian Romances of Chrétien de Troyes), Pinnacle Press (24 May 2017)

- De Troyes, Chrétien (1177-1181) Yvain: or the Knight of the Lion, trans. Kline A. S (The Arthurian Romances of Chrétien de Troyes), Independently published (25 Jan. 2019)

- De Troyes, Chrétien, Arthurian Romances, trans. Carroll, Carleton & Kibler, William, Penguin Classics; New e. edition (31 Jan. 1991)

- Freeman, Michelle A. (1979) The Poetics of “Translatio Studii” and “Conjointure”: Chrétien de Troyes’s “Cligés,” Reviewed by Maddox, Donald, Speculum, Vol. 55, No. 3 (Jul, 1980), pp. 569-572 (4 pages) Published By: The University of Chicago Press

- Hedesan, Jo, (2009) The Four Stages of the Alchemical Work, Esoteric Coffeehouse (web site), 26th Jan, 2009

- Levy, Raphael, (1956) The Motivation of Perceval and the Authorship of Philomena, PMLA, Vol. 71, No. 4 (Sep., 1956), pp. 853-862 (10 pages)

- Lotze, Ingrid, (2013) The Prologue to Chrétien’s Erec et Enide: Key to the Alchemical San of the Romance, ARCANUM: Journal of Esoteric Currents during the High Middle Ages, No. 1 (2013), pp 1-13, Eagle Hill Institute

- Maclean, Adam, Liber de compositione alchemiae (The Book of the Composition of Alchemy) (after c. 668 – c. 704 A.D.) by Morienus, The Alchemy web site on Levity

- Maclean, Adam, Tabula Smaragdina (The Emerald Tablet) (between c. 200 and c. 800), The Alchemy web site on Levity

- Maclean, Adam, Turba Philosophorum (Assembly of the Philosophers) (c.900A.D.), The Alchemy web site on Levity

- Reichert, Misha Brasher, (2003) Between Courtly Literature and Al-Andaluz: Oriental Symbolism and Influences in the Romances of the Twelfth-century Writer Chrétien de Troyes, University of Minnesota, 2003

- Sharpe, Thomas (November 30, 2020) Magister Amalricius, Issuu Digital Publishing Platform

- Sharpe, Thomas (December 30, 2020) The Templecombe Head, Issuu Digital Publishing Platform

- Stein, W. J. (1928) The Ninth Century and the Holy Grail, Temple Lodge Publishing; 2nd edition (29 Sept. 2009)

- Stein, W. J., (192?) Thomas Aquinas and the Grail, Die Drei, Vol. VI., No. 9 (Stuttgart).

- Suhrawardī, Yahya ibn Habash (12th Century) The Shape of Light, trans. Al-Nur, Hayakal, in Suhrawardi: The Shape of Light, Fons Vitae, US; 2nd Printing ed. edition (19 Jan. 2001)

- Wood, Juliette (2012) The Holy Grail: History and Legend,University of Wales Press; First Edition (15 Nov. 2012)

Image Source

- Early alchemical ouroboros illustration with the words ἓν τὸ πᾶν (“The All is One”) from the work of Cleopatra the Alchemist in MS Marciana gr. Z. 299. (10th Century), (commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Chrysopoea_of_Cleopatra_1.png)

- Erec and Enide with Sparrowhawk: Deutsch: Codex Manesse, UB Heidelberg, Cod. Pal. germ. 848, fol. 69r, Herr Werner von Teufen (https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Codex_Manesse_069r_Werner_von_Teufen.jpg)

- Aludel apparatus in, The Keys of Mercy and the Secrets of Wisdom, an alchemical work written by Mu’ayyad al-Din al-Tugra’i (1062-1121). Arabic manuscript in the Library of Congress. Courtesy of Maclean, Adam, The Alchemy web site on Levity.

- Yvain and Lion, Psautier, avec cantiques et litanies. Source: gallica.bnf.fr. Bibliothèques d’Amiens métropole, . 18, fol. 67r. (http://jessehurlbut.net/wp/mssart/?manuscript-id=bibliotheques-damiens-metropole)

- Sword-Bridge, Lancelot-Graal, [de Gautier Map]. Source: gallica.bnf.fr Bibliothèque nationale de France, Département des manuscrits, Français 119, fol. 321v. (http://jessehurlbut.net/wp/mssart/?tag=lancelot)

- Perceval arrives at the Grail Castle, to be greeted by the Fisher King. From a 1330 manuscript of Perceval ou Le Conte du Graal by Chrétien de Troyes, BnF Français 12577, fol. 18v. (https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Perceval-arrives-at-grail-castle-bnf-fr-12577-f18v-1330-detail.jpg)